NIGHT RAT: Underground in MTL

by Kyra Sutton

Photos by Mie Beers

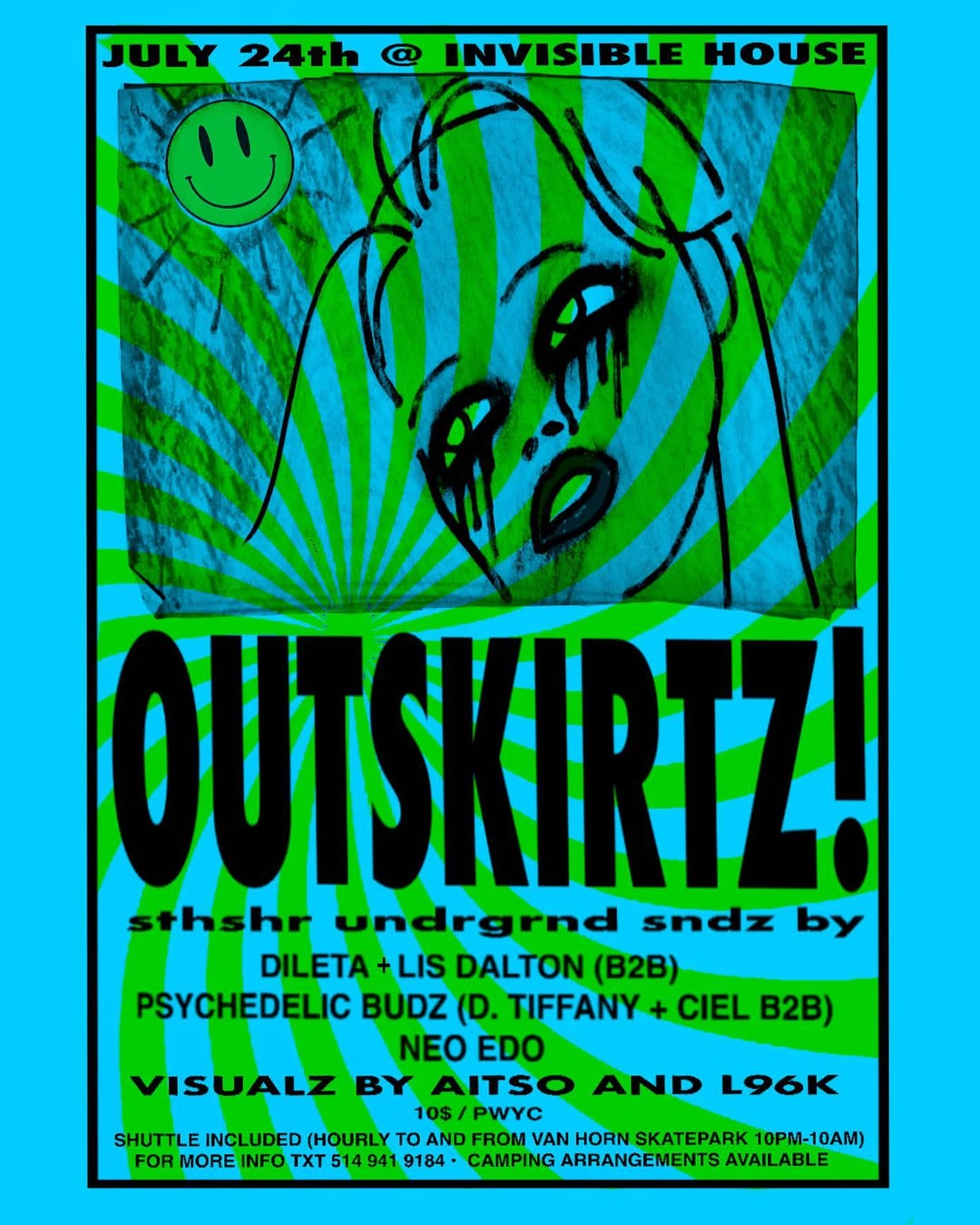

002 / Echoes from the Outskirtz

Cover photo by Mie Beers, 35 mm film.

The year is 2021. It’s a Friday, and like many Fridays around this time, you have no plans but to gaze far out of your bedroom window, dissociating from time’s brutal continuity, until the street tapers off into oblivion. Your friend calls you— there’s a rave happening just outside the city and they’re all going. You protest: you have nothing to wear, no money, no way to get there, and despite your best efforts not to lose your grip on reality, you’ve completely forgotten what it’s like to exist inside a body that others must perceive, must interact with.

“For 10 bucks we can take the party bus.”

Curiosity sparks in your chest. You hear yourself asking where.

“Meet us at Van Horne skatepark. Come on.”

You watch a car’s shadow darken the window— it reminds you of the nighttime, fleeting and full of speed— that dimension of the outside world you’d forgotten about. A ghostly urge to move passes through your limbs, where boredom has begun to burrow into your bones. It feels like the first hint, in forever, at the possibility of fun. What’s most exciting about the rave is always the before, the build-up, when you have no idea yet where the night may lead. So you go, before you can talk yourself out of it, before you can factor in all the rules you might be breaking.

Two hours later, you’re crammed into a blacked-out U-Haul with your friends and fifteen or so other people you’ve never met, crouching down as you hurtle over the Champlain bridge, fingers crossed that no one pulls you over.

The truck is pitch dark, filled with smoke. People are chatting, lighting cigarettes. Some are wearing masks. Some look nervous, holding tightly onto their friends. And some look elated — eyes wide, glinting open — as though they’ve been waiting weeks for this moment. To be the tiniest bit transformed. To feel a dark red glow.

The Delson Tapes

“The Delson situation was very unique,” Adam tells me over coffee, one of the few occasions I’ve seen him in the daylight, outside of a rave. A key behind-the-scenes figure in the city’s underground music scene, Adam Cathey (he/they) moved from Vancouver to Montreal in 2017. At the time, he was in possession of various vehicles, since he operated a moving business in the city with his friend Cole. Disillusioned by the isolation of COVID, he found a property to rent just outside the city in a small, unsuspecting town in Quebec called Delson. “There was really no point to living in the city if you couldn’t see anyone,” he says. Adam’s friend Eva accompanied him on the initial visit to the house, posing as his wife so that he would seem more credible to the owners.

Mira and Virginia at Delson. // Adam and Cole.

And then, Adam got the idea to throw raves at the house. “The core organizing crew was me, Cole, his partner Mira, and my friend Virginia, also from Vancouver,” Adam explains. For the first couple parties, they collaborated with Simon Rock and Nicolas Levy (STM Underground). The Delson raves were branded as “Outskirtz,” with Adam dubbing the venue, Invisible House. “That never really caught on,” he says. “Everyone just called it Delson, which I hated.”

Montreal artist Mira Sophia Dasilva, one of the core crew members of Outskirtz, commented on the Delson house: “To us it wasn’t just a rave spot, it was our home, the place where we’d sing karaoke, have bonfires and weird movie nights.” Now a regular face in the city’s nightlife circuit, she shared how Delson was her first venture into organizing: “The experience was chaotic, often stressful, but also incredibly fun. What started as small gatherings gradually grew into something bigger. This was my first time being part of something like this, and honestly, I had no idea what I was doing."

Mira designed the posters to promote the raves.

Most of the people that you ask about Delson will firstly remember the same thing— the journey. “I think what was so special about it was that it wasn’t in the city, it was far away. It really felt like an experience, going to Delson,” local writer and raver Alana Dunlop recalled of her nights there. “We would meet under the Van Horne bridge. They would squeeze like ten people in these trucks and drive for 30 minutes on the highway, bending down so no one could see that there were more people than there should be.”

“It was such a different vibe from any rave I've been to.” Quinn Farncomb, one of the attendees of the Delson parties, similarly remembers the transportation. “We were just hoping to God the cops didn’t pull us over. The trucks were pretty rundown,” Quinn said. “There were holes in the floor where you could see the highway beneath you.” The trucks ran back and forth for a couple hours, shuttling people from the city to the house in Delson. Afterwards, rides back to Montreal started again in the morning. Everyone was camped in Delson for the night, creating the atmosphere of a festival. The organizers threw blankets and pillows in the back of the trucks for people to go to sleep and lit a bonfire on the lawn, where Quinn recalls sitting and chatting with strangers. For the last Outskirtz party, Adam upgraded to a full-sized bus to transport everyone to the party.

Alana was impressed at the organizers’ ingenuity in transforming the house into a venue: “They put a lot of effort into the layout of the rave— it wasn’t just like dancing in someone’s garage. They had visuals projected onto walls. They set up multiple chill areas, one of them inside a U-Haul.”

Chill area inside U-Haul. // Alana and friends at Delson.

Photo courtesy of Mie Beers.

“The space was very interesting. I guess it had the vibe of a barn-burning party,” Adam laughs. Their metaphor conjures images of countryside teenagers running into the woods at dark, chanting around a roaring bonfire, offering up their dancing bodies to the moon. “There was a river down the road, and a cemetery across the street, where people would go and hangout.”

The Delson crowd was generally composed of familiar faces, people that Adam already knew from going out. Promoted mainly on Instagram, they estimate that most of the raves had around 300 people in attendance. The DJs that played included Honeydrip, Anabasine, Neo Edo, Softcoresoft, Mossy Mugler, Pretty Privilege, and others. Over the course of summer 2021, they hosted five raves in total, and received several fines for noise complaints and breaking COVID restrictions. Though the cops showed up at every Delson party, the final time was especially harsh due to a noise complaint that Adam suspects was called in by a competing party.

The Delson raves were completely DIY, organized solely with the help of Adam’s friends and volunteers. They kept the ticket prices at $15, just enough to pay the DJs and cover their expenses. “I never thought of it as a good business idea, or treated it like a money-making scheme. I just wanted it to be about celebrating people’s talents, finding creative DJs,” Adam explains. “There was a need for each other, for connection.” And some even found love. Adam’s friend Soline, who was working the door one night, met someone who would become her husband.

“Adam’s love of bringing people together created Outskirtz,” Mira commented. “I met my partner at the Delson spot, and some of my greatest friends. It only made sense to bring the rest of Montreal.” Reflecting on this time period, she added, “I think we all needed to feel a sense of freedom, and that’s what made it so special. What stands out most in my memory are the nights spent falling asleep in the basement, bass thumping through the walls, waking up to an empty space covered in bags and cans, knowing we had a long cleanup ahead.”

Mira at Delson.

Montreal DJ and icon of the queer rave scene, Pretty Privilege, also recalled the Delson parties fondly: “It felt like a little getaway that we all took together. There was a magic and secrecy to it that feels a lot rarer now.” She shared how significant these events were for her: “Some of my happiest rave memories are from Delson. It’s not where I started raving but it’s where I started doing it seriously. Met so many friends, played my first set that I was proud of. Truly so influential for how the rest of my Montreal life would turn out.”

Beyond the Warehouse

After summer 2021, the Delson crew took a break from organizing; Adam and Virginia moved back to Vancouver for some time. When Adam returned to Montreal in September 2022, he found a warehouse space to move into through the help of a friend. Since the space was poorly maintained, totally decimated by water and mold, Adam paid very little in rent. At the time, he was working for a clothing factory, which gave him access to a variety of new clothes that were being thrown away due to minor flaws, including some designer items. This sparked the idea of starting a thrift store. Located in that industrial margin, in between where the Plateau drops away and the Mile End has not yet begun, this warehouse would become the new space known as “Outskirtz.”

A hybrid of clothing-store, jam-space, rave venue and community hangout spot, Outskirtz was Adam’s vision for the fusion of queer fashion and parties. Originally, they imagined it as a kind of “communal closet” space, where people could come try on different items and get ready together, as a pre-party. “I wanted it to be about celebrating fashion in a non-consumerist way,” they explain. They thought about operating a library for the clothes, in which people could wear something and return it later, or request to be styled. Also selling books, electronics, and the oddest assortment of artifacts you’ve ever seen, visitors could dig through the racks at Outskirtz for hours and still find more items to be curious about. With a DJ booth set up on a stage, mannequin heads and torsos displayed behind metal grates, and Tetris Attack playing on an old video game console, Outskirtz was an eccentric space that I was grateful to frequent.

Me at Outskirtz in 2022.

On my first visit to Outskirtz, I picked out a pink dress with a minor fray in the hem. “A factory defect,” Adam told me. After a brief negotiation that consisted of Adam suggesting very low prices and me replying “Sure,” I bought the dress and four other items for a total of $15.

The Outskirtz friperie.

During its run, Outskirtz hosted a variety of events and purposes. Unfortunately, its existence was short-lived, as Adam and the rest of the artists in the warehouse were forced out by the building’s owners in December of 2022. Originally, the landlord was receptive to Adam’s vision, suggesting that he take over the space and convert it into a cultural centre. However, the landlord’s daughter, who assumed ownership of the property, rather wanted to sell the space to Audi and viewed Adam as a threat. Now, the building is being torn down to build a parking lot.

Since then, Adam’s stock has been kept in Yota (Y.O.T.A.), the next evolution to come after Outskirtz. Inspired by similar values, Yota was a pseudo-squat collective based in another warehouse, founded shortly after Adam left the Outskirtz space. Yota hosted parties and community activities, and featured a pole dance room, DJ and sound equipment, and Adam’s clothing friperie. “We had permission to be there, though it wasn’t technically legal,” Adam clarifies. The Yota space was maintained through frequent meetings with keyholders, to organize all aspects of the collective and manage security concerns; as the groundskeeper, Adam attended every meeting.

However, over time, the Yota space was difficult to maintain. “There was an incident that set off a fire alarm, and we got kicked out. They changed the locks on us. I took it pretty hard. All of my stuff is still in there— I haven’t been able to retrieve it. It feels like all the effort I put into it is gone,” they sigh. “I still have a thousand copies of the same floral black dress in there that I’d been trying to get rid of!” Though the warehouse was lost in June of 2023, the Yota collective is still organizing and looking for a new space.

I ask Adam what’s next for them after the fallout of these projects. “I’m more interested in space-building,” they respond. “Since I was twenty, I’ve illegally lived in warehouses.” Honing in on their passion for community, they want to create more spaces like Outskirtz and Yota. “I’ve always found community in and around music. It’s always been super precious to me,” they say. Adam became involved in the music scene as a kid, organizing their first events as young as twelve years old— now, they’re forty. A musician in their own right, Adam plays a variety of genres, like grunge, punk and electronic music. “If you kill a space like that," he says, "you just killed 500 artists out of the city.”

Adam reflects on how there used to be many more spaces like Outskirtz and Yota in the city; they recall La Plante, a pseudo-squat institution in the Mile End for artists and marginalized people, and a variety of warehouse spaces and artist lofts that hosted parties. “It’s very hard to come by anymore,” Adam remarks, in regards to the city’s gentrification of warehouse buildings, converting them into high-end condos. Bâtiment 7 stands out as a notable victory— this massive warehouse was converted into a community center by the neighbourhood collective, who assumed legal rights to the building in 2016, after 14 years of protest. (1)

However, due to Montreal’s increasingly hostile policies towards DIY spaces and nightlife, it’s become very difficult to organize events in well-populated areas. The SPVM’s “Morality Squad” are cracking down on nightlife activities all over the city, even raising noise complaints with established venues like the SAT and New City Gas. As it goes, underground spaces are pushed further underground. “I want to get a rave bus going,” Adam laughs. “Get the population out to industrial zones and throw raves there,” he says, inspired by the Delson era.

Though the Outskirtz concept was short-lived, its radical potential still resonates with me years after. Outksirtz was one of my first ventures into alternative space. A couple years later, I attended another event at the same warehouse, a DIY poetry reading organized by other artists in the building. I remember how, when you approach the lot from the corner, there’s a rift in the landscape—a car dealership springs up on the opposite side of the street, the underpass echoes beyond you. Everything looks more angular. The warehouse seems strange, suddenly there, sunken into itself, its dilapidated wooden porch jutting out against all the grey. When you enter, you understand that the building is abandoned— an industrial symptom of something that failed, was forgotten about, given up halfway through. A thick layer of sawdust collects on the open floors, patched over with wooden planks. Bricks tumble from the walls. Air flows through the ventilation pipes in strained, heavy groans, like something breathing its dying breaths. But if you look a bit closer— Christmas lights wrapped around ceiling beams, canvases hung over holes in the walls, whispers of friends trying on clothes, warehouse ghosts slipping in and out of hidden rooms— you know the space is cared for. The artists are at work. Their ideas generating fuel, firing heat through the busted pipes. Musicians spark the electrical wiring, rumbling the cracked drywall with their thundering instruments. The whole warehouse courses with energy, thrumming, on the verge of collapse. And even as the walls crumble down and the floors disintegrate, the music plays on. The dancers keep dancing. The painters still paint.

1. Colpron, Suzanne. “Il faut sauver le Bâtiment 7.” La Presse, La Presse Inc., 9 Dec. 2018, plus.lapresse.ca/screens/731bba7a-96ec-4fbf-90e1-5847cc7d7b85__7C___0.html.